Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Ellenbrook

Though its precise origins are uncertain, Ellenbrook chapel possibly existed in the early 13th century. It is not known whether a contemporary reference to a chapel at Worsley referred to Ellenbrook chapel, or to another chapel in the hall of the lords of Worsley. It was an outlying chapel within the parish of Eccles, the nearest churches being at Eccles, Leigh and Deane in Bolton. It was probably established through a grant from the Benedictine Abbot of Stanlawe Abbey (on the Mersey estuary) to Richard de Worsley, with the Benedictines staffing the chapel and paying sixpence a year to Eccles church to acknowledge the chapel’s subsidiary status. The monks later moved from Stanlow to Whalley Abbey. The photograph below shows the chapel alongside the brook.

The photograph below shows the war memorial in the garden at the rear of the chapel. It was moved in 2019 to the front of the chapel so it could be seen from the main road.

The chapel is located opposite the boundary stone which marks the division between the Hundreds of Salford and West Derby, and the point at which the three townships of Worsley, Little Hulton and Tyldesley meet. Ellenbrook was also the boundary of the ancient parishes of Eccles and Leigh. The lettering on the stone was obliterated during the second world war to prevent it being used by enemy spies, and today only its head shows above the pavement (picture below). It was from the Red Lion at Ellenbrook that the traditional walking of the boundary of the Worsley manor commenced.

In 1581, the chapel was endowed by Dorothy Brereton. Dorothy, daughter of Sir Richard Egerton of Ridley, Cheshire had married Richard Brereton of Worsley and Tatton, Lord of the Manor of Worsley, in 1572. Richard died in 1598 and was buried in Eccles Parish Church, and Dorothy married Sir Peter Legh of Lyme Hall, Cheshire in 1604. She was widowed again in 1636.

Dame Dorothy Legh died in 1639 and was buried in Eccles church. She bequeathed £400 to Ellenbrook chapel to buy Common Head Farm at Mosley Common, the income from which established Dame Dorothy Legh’s Charity, which continues today. Following a legal dispute in the 1650s, it was determined that the charity would support the minister of Ellenbrook chapel and the local poor.

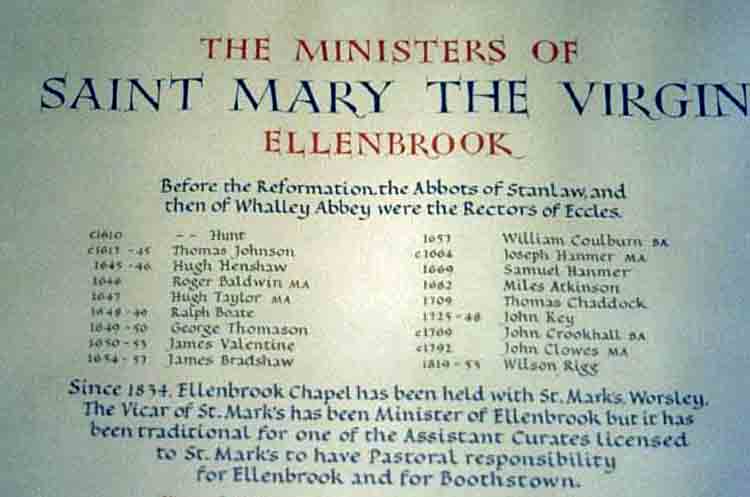

The first known minister at Ellenbrook was a Mr. Hunt in around 1608. The chapel was not continuously served by a resident minister and during the 17th century numerous ministers were associated with Ellenbrook, many for only a few months. Of these, the longest-serving was Thomas Johnson whose service of some 30 years ended around 1646. Johnson was a renowned puritan, who left Ellenbrook to become Rector of Stockport until his death in 1656.

Perhaps the most notorious of the 17th century ministers was William Coulburn, who was at Ellenbrook from 1657 to around 1663. In 1663 he was arrested, possibly for trying to steal money through confidence tricks, an act which he perpetrated in various other parts of England in subsequent years. Despite numerous question marks over his character, Coulburn returned to Lancashire as minister at Mottram-in-Longendale, where he was buried following his death in around 1697.

John Egerton, 2nd Earl of Bridgewater left Worsley to his second son, Sir William Egerton, who married Honora Leigh; their only son predeceased Sir William. Worsley passed to Honora for the period of her lifetime. She later returned to Worsley Old Hall having been taken from a London asylum to marry Hugh Lord Willoughby, who had been attracted by the estate. Willoughby was a dissenter who, in 1697, sought to convert Ellenbrook chapel to non-conformism by locking out the minister, Miles Atkinson, and installing John Cheyney. Atkinson himself came to a mysterious end, believed to have been murdered; he left his parish in Wirral in 1704, and was last seen near Leeds riding a white mare.

In 1719 the income of Ellenbrook chapel was £23-6-3d, of which £17 was rent for the house and grounds. The old chapel was demolished and rebuilt in brick in 1725. The chapel was visited by the eight year-old Clive of India in 1733.

A gallery was built in the chapel in 1816. In 1828 Samuel Newton, who had been clerk to the chapel for 44 years, died; he became one of only three people to be buried in the church grounds. Samuel Newton had lived in a cottage near the chapel and wished to be buried close to home. At that time the resurrectionists (body-snatchers) were at work, so Newton was laid in a deep grave covered with a number of heavy stones.

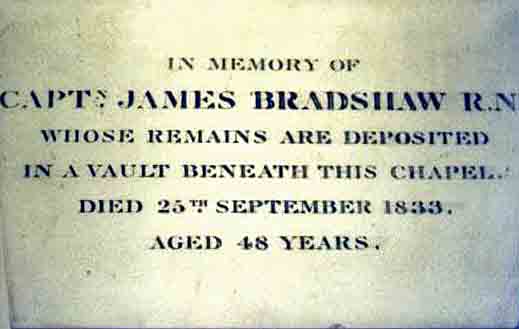

In 1833, Captain James Bradshaw committed suicide; he was the son of Robert Haldane Bradshaw, Superintendent of the Bridgwater Trust and a local landowner. James Bradshaw cut his own throat when he was overlooked by his father as his appointed successor as Superintendent of the Trust. Local tradition states that because of his suicide Captain James Bradshaw was buried outside the eastern side of the church grounds, though his father bought the land, and the chapel was extended to cover his grave. This is why the road between the church and the (now former) Red Lion inn is so narrow, and why a new road by-passing the hamlet of Ellenbrook had to be built to serve new housing in the 1980s.

The chapel was restored in the 1860s, though the 2nd Earl of Ellesmere died before his restoration project was complete. The chapel’s organ dates from this time – a memorial to the Earl. In 1865 the final burial in the grounds occurred, following the death of Peter Walker, who had been clerk to the chapel since the death of Samuel Newton.

In 1894 the chapel was described by the verger of St. Paul’s, Walkden in the Eccles Advertiser. He told of the burials of Samuel Newton and Captain Bradshaw, and wrote that “Ellenbrook chapel 150 years ago was a thatched building; it has often been rebuilt”. St. Mary’s Ellenbrook was licensed to perform marriages in 1972, and the first wedding for 127 years took place there. Pictured below is the inside of the chapel today.

https://www.stmarysellenbrook.co.uk/

Acknowledgements

This web page was compiled by Tony Smith and drawn from notes supplied by Mrs. C.E. Mullineux, an account of the 17th century ministers by Ernest Axon (1920), and Boothstown: A Chronological History by Carol Woodward, published by City of Salford Libraries and Information Service, Arts and Leisure Department, 1994. Photographs by Tony Smith.