Memories of Boothstown in the 1950s by Derrick Cunliffe

On Chaddock Lane south of the East Lancashire Road, there is a row of terraced houses facing south. At one time these had a clear, unbroken view across Chat Moss. The few houses that stood on the south side of Chaddock Lane are still discernable from their Victorian architecture; one of these was converted into a grocery and sweet shop, and it is still in business on the corner of Linden Road. Linden Road, which extends south from Chaddock Lane, used to be called Engine Row, and was a narrow cul-de-sac, about 200-300 yards long, at the end of which was a small terrace of houses facing east across open fields to Boothstown village. A little further on had been the Chaddock Colliery in former times. In one of the houses on Engine Row lived our milkman, Fred Millard, who was quite a character.

Further along the south side of Chaddock Lane, towards Boothstown, there stood the Co-op shop, which poked out of the field and stood on stilts. The modern houses that replaced it can be seen well below the level of the road. On the field to the east of the Co-op, young people used to practise riding and jumping on horses and ponies. Some of them gave good displays, and on pleasant summer evenings I used to walk down the road to join the spectators on the wide pavement. I think we all thought that this would develop into a regular equestrian show with a Boothstown fair, but the landowners had other ideas.

Facing the field on the north side of the road was a row of terraced houses (still present today), one of which had been converted into a shop. It was run by Mr Smith, the cobbler. Apart from mending shoes, boots and clogs, he could turn his hand to repairing all sorts of leather goods, including belts and ladies’ handbags; he could even mend mechanical things, such as clocks that the jeweller had declined to repair.

Further down, at the junction of Mosley Common Road was the CWS shop, dated 1920. I do not remember any activity at this shop, but across the road opposite the Methodist chapel was our greengrocer, Mr Markland. We never needed to visit this shop because the son, Rodney, used to drive round in a lorry with the fruit and vegetables nicely displayed alongside the weighing scales. He had a leather bag strapped over his shoulder for money and change. Rodney used to reverse up the drive to the back of our house, so that mother only needed to step outside with a shopping basket.

The next shop after Markland’s was some sort of food retailer; I recall it being popular with people calling in for a tasty lunch to take back to their workplaces. Then there was Barclay’s Bank, subordinate to the branch in Tyldesley; it was not used very much, and its opening hours were cut back to make it almost useless before it was closed down.

Across the road was the ironmonger at Star House. The shop had everything from bags of “Boltonite” manure to oil lamps. It was crammed from ceiling to floor, and behind the counter there was a trap door through which more goods could be fished out of the cellar. There was only room to serve one customer at a time, and you had to be careful not to knock anything over.

I cannot remember the scene before Ridgemont Drive was created, but I do remember Stirrup Brook bridge with the boundary mark. Between here and Barclay’s Bank was a row of three terraced houses, and the end one overlooking the brook was an off-licence run by Jack Ratcliffe, his wife and their young daughter. The door was at the corner of the shop, up two or three large steps. Jack also sold cigarettes, cakes and bread; he had a display of sweets on his counter, and shelves of bottles, jars and packaged goods behind.

Unger’s canning factory was in a converted cotton mill. It was easy to drive a lorry into the loading bay, and I sometimes went with the driver to pick up large wood boxes that had come in full of fruit. We used the thin timber for making trays for seedlings and bedding plants at the nurseries [Derrick’s family ran the Worsley Hall Garden Centre]. At the rear of the factory was the workers’ garden in the Delph that extended up to the East Lancashire Road – it was here that a hoard of Roman coins was found in 1947.

Next door to the canning factory was Yates’s cotton mill, with a post-war annex that came right up to Leigh Road, forcing pedestrians to cross over onto a narrow pavement. Here I used to sit just inside the open door of the spartan barber’s shop where Jack Hankinson cut hair at a snail’s pace, while talking and debating with his older clients. I spent hours watching out of that door: Yates’s loading bay was directly opposite, and could take one lorry at a time. The bigger or longer the lorry, the more awkward it was to reverse into the narrow entrance, and of course all traffic came to a standstill.

There was another shop next door to the barber’s, though I no longer remember what it sold – the pavement was too narrow to stop and look in comfort anyhow. On the corner was Lloyds, our newsagent, where we bought our fireworks leading up to 5 November. This row of shops has long since gone; the site is now grassed over with a gas substation in the background. On the opposite corner of Victoria Street was Prescott’s grocery and bakery. Pictured below is the entrance to Victoria Street and corner shops, seen from the yard of Yates’s mill.

Across Leigh Road from here were two narrow lanes, side by side. One went round Yates’s mill, and the other (to the right) went up to Aspull Engineering. The lane to the engineering works passed the builder’s yard and workshop of James Mather & Son, run by Bill Mather, and the premises of Frank Andrews, the village blacksmith. As you may expect, Frank was of broad build; he wore a dirty cap on his large, round balding head, and he wore spectacles. The skin on his head and arms was ingrained with dirt, that seemed impossible to wash out completely. I was too young to have seen Frank shoe horses, as he became more of an engineer after the war; he attended night school well into middle age to learn about new types of metals and about ways of working them. He liked to learn unusual words, especially long ones, then baffle everyone with his vocabulary.

The demarcation line between Frank’s and Bill’s land altered from time to time according to the state of their friendship. One day, after the workers had gone, Bill went into his workshop to complete some timber pieces on his circular saw. While he was working Bill became distracted, and within a second the saw had cut off four of his fingers, and the top of the thumb on his right hand. Fortunately, he lived in a bungalow adjoining his workplace, so his wife soon fetched help.

In many ways Bill was ahead of his time. He built a long hut on his boundary which stretched Frank’s vocabulary to its limits, and he stocked it with all kinds of hardware, laid out on counters and on shelves. We were able to obtain, by the pound, certain types and sizes of nails, screws or washers; there were all sorts of hammers, screwdrivers and saws; it was all quite novel in the 1950s.

Apart from the Post Office, which was run by another branch of the Lloyd family, that was really the end of Boothstown to me. We always used Simpson Road to go through the village; the old Leigh Road had been left without tarmac, so that cyclists like me were tempted to avoid it.

One place I was often sent on errands was to Mr Fitzpatrick’s, at what seemed to be the last place in Boothstown, down Vicar’s Hall Lane. A man of serious demeanour, his main business was rubber. I rarely saw his wife and children. His house must have been a fine place at one time, but it was neglected and in need of repair. The stables were full to the rafters of hosepipes and reinforced belting of all sizes; it seemed so disorganised, but he could always find what I wanted. The large garden at the back was buried under high mounds of rubber coils, and lengths of all description. Loads of it had lain undisturbed for so long that it was obviously rotten. To get between these mountains of rubber one walked carefully on thick rubber-matted paths. When it came to parting company with him, no matter how much or how little was bought, he always gave a gift of something. Over the years I ended up with many neat cuts of reinforced rubber for cleaning windows, and many odd decorated plates and cups.

1950s Photographs

The photograph below was supplied by Janice Cunliffe and shows a fancy-dress parade circa 1953-1955. The building to the rear and left of the picture is the rear of the old Co-op building on Chaddock Lane. Janice is at the front wearing “Time Waits for No Man”.

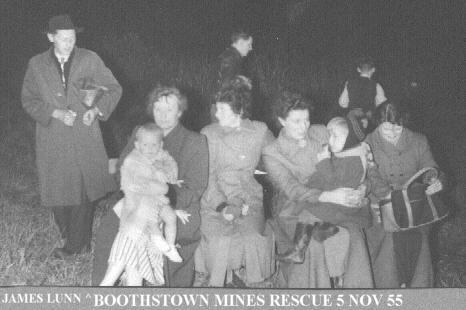

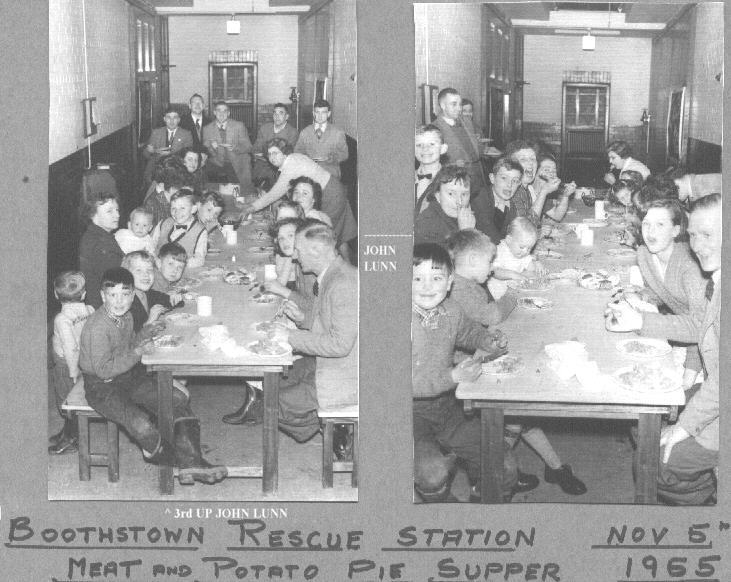

The following set of photographs was kindly supplied by John Lunn (no relation to the Astley historian referred to elsewhere on this web site). John spent much of his childhood living on Ellenbrook Road in Boothstown, indeed his grandfather built a number of the houses on Ellenbrook Road in the early 1930s.

The two photographs below show the Whit Walk of 1955 gathering on the forecourt of the Mines Rescue Station on Ellebrook Road.

The photograph below shows an enamel plate, the like of which was a common site around Boothstown and Worsley.

The photograph below was taken at the Bonfire Night party on 5 November 1955 at the Mines Rescue Station.

The photographs below were also taken at the Bonfire Night party on 5 November 1955 at the Mines Rescue Station, and show the children enjoying their hot pot supper.

Acknowledgments

Memories were written by the late Derrick Cunliffe, formerly of Chaddock Hall, Boothstown. The photograph from Yates’s yard is from collection of Walkden Library. Other 1950s photographs were kindly provided by, and are the copyright © of, Janice Cunliffe and John Lunn, as described. This web page was compiled by Tony Smith.